When you’re making a database engine, you need to correctness seriously. That’s why Dolt has lots of correctness tests, of all types. In addition to running standard conformance tests like TPC-C and SQLLogic, we also have around 90k tests written in Go. This includes our Plan Tests, where we set up a database, write a query, and then check that the generated query plan matches what we expect.

Query tests are brittle: unrelated changes can cause slight perturbations in the exact text of the query plan, which causes the tests to fail. When this happens, we examine the changes and verify that the new plan still makes sense. It’s not a perfect system: brittle tests are a code smell. But they giving us insight into the inner workings of our SQL engine that end-to-end or unit tests can’t. They also guarentee that a code change won’t affect query plans without us noticing and ensure that our plan generation is deterministic consistent across platforms.

Last week, we fixed a performance issue, and this allowed us to re-enable a set of plan tests that had previously been disabled. As was expected for plans test that hadn’t been run in a while, a couple of them were failing. After inspecting that the new generated plans still looked correct, I regenerated the tests, made a PR, and ran Continuous Integration.

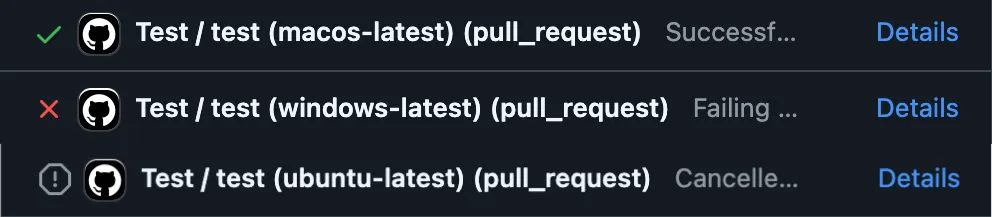

Like any principled team, we use CI to gate changes. Specifically, we use GitHub Actions to run our full test suite on every PR, and we run these tests in a variety of different contexts, such as different operating systems. This was the result of the CI for the PR:

| Test Suite | Result |

|---|---|

| Test / test (macos-latest) | Successful |

| Test / test (windows-latest) | Failing |

| Test / test (ubuntu-latest) | Cancelled |

Differences between operating systems isn’t unheard of, which is exactly why we run all these different configurations. But they are eyebrow raising when they happen, because Dolt is almost pure Golang, which is pretty reliably cross-platform.

We’re not entirely platform independent: a small amount of our networking code is platform-specific, And we depend on C libraries for regex parsing.

But in the case, the tests were failing because our plan tests were generating different execution plans on different platforms. This was the last place I expected the platform to matter because query planning is purely algorithmic: it doesn’t touch the filesystem or networking or anything else where you would expect to find OS-specifc code.

One of the reasons I love working on compilers, a category which includes query planners, is because it’s one of the few computer science disciplines that’s purely functional and abstract: source query goes in, compiled plan comes out. It works by generating trees that represent different possible execution plans, and applying a cost function to each one to identify the plan with the minimal cost. It’s all math: the messy reality of your hardware doesn’t matter. Your OS doesn’t matter. The optimal query plan is the optimal query plan regardless of the environment that’s running the analysis.

And yet, the tests seemed to indicate otherwise. But why?

The Investigation#

My first step was to confirm this behavior outside of GitHub Actions. Maybe there was something really weird going on with our action runner?

I use a Mac for local development, so it was easy to confirm that my local results matched CI results for Mac. Getting set up on a spare Windows machine was a bit harder because Dolt depends on the ICU4C libraries, and linking them currently requires a specific setup. I miss the days when Dolt was pure Golang; you can read more about our decision to embrace CGO and the trade-offs involved here..

Once I was able to indeed confirm that Windows and Mac were creating different execution plans, I needed to figure out why. I compared the plans generated by the tests for clues. Here’s an example of one of the smaller diffs, a join of three tables:

Diff:

--- Expected

+++ Actual

@@ -14,5 +14,5 @@

│ │ │ │ ├─ (ct.id = mc.company_type_id)

- │ │ │ │ ├─ LookupJoin (estimated cost=557228.100 rows=168857)

- │ │ │ │ │ ├─ LookupJoin (estimated cost=557248.800 rows=168857)

- │ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ (t.id = mi.movie_id)

+ │ │ │ │ ├─ LookupJoin (estimated cost=557248.800 rows=168857)

+ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ (t.id = mi.movie_id)

+ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ LookupJoin (estimated cost=557228.100 rows=168857)

│ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ LookupJoin (estimated cost=523477.800 rows=168857)

@@ -48,15 +48,15 @@

│ │ │ │ │ │ └─ Filter

- │ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ ((mi.note LIKE '%internet%' AND (NOT(mi.info IS NULL))) AND (mi.info LIKE 'USA:% 199%' OR mi.info LIKE 'USA:% 200%'))

- │ │ │ │ │ │ └─ TableAlias(mi)

- │ │ │ │ │ │ └─ IndexedTableAccess(movie_info)

- │ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ index: [movie_info.movie_id]

- │ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ columns: [movie_id info_type_id info note]

- │ │ │ │ │ │ └─ keys: mc.movie_id

+ │ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ (cn.country_code = '[us]')

+ │ │ │ │ │ │ └─ TableAlias(cn)

+ │ │ │ │ │ │ └─ IndexedTableAccess(company_name)

+ │ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ index: [company_name.id]

+ │ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ columns: [id country_code]

+ │ │ │ │ │ │ └─ keys: mc.company_id

│ │ │ │ │ └─ Filter

- │ │ │ │ │ ├─ (cn.country_code = '[us]')

- │ │ │ │ │ └─ TableAlias(cn)

- │ │ │ │ │ └─ IndexedTableAccess(company_name)

- │ │ │ │ │ ├─ index: [company_name.id]

- │ │ │ │ │ ├─ columns: [id country_code]

- │ │ │ │ │ └─ keys: mc.company_id

+ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ ((mi.note LIKE '%internet%' AND (NOT(mi.info IS NULL))) AND (mi.info LIKE 'USA:% 199%' OR mi.info LIKE 'USA:% 200%'))

+ │ │ │ │ │ └─ TableAlias(mi)

+ │ │ │ │ │ └─ IndexedTableAccess(movie_info)

+ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ index: [movie_info.movie_id]

+ │ │ │ │ │ ├─ columns: [movie_id info_type_id info note]

+ │ │ │ │ │ └─ keys: mc.movie_id

│ │ │ │ └─ HashLookupIt’s not immediately obvious because of the number of changed lines, but the two plans are actually very similar. The engine is selecting the same indexes in both plans, but two of the tables have been swapped in the join order. A couple of other things also stand out:

- The first join has the exact same estimated cost, and the exact same number of expected rows in both plans. This suggests that both plans have very similar performance characteristics. The tables being swapped are likely the exact same size and there’s no strong signal telling the planner how to order them.

- The cost estimates for the full query are almost equal, but not quite.

The other failing tests were similar: Mac and Windows would produce different plans, but neither plan was obviously better than the other. Sometimes the difference was in the join order, other times it was picking between two effectively equivalent indexes, or two different ways of expressing the same filter condition. In every case it was not obvious which plan was “correct”, and the choice was effectively arbitrary.

I briefly wondered if this had something to do with a collection having a nondeterministic iteration order. But if that were the case, we’d expect different results between successive runs on the same machine, instead both platforms were deterministic but disagreed with each other.

I needed more data to understand not just which plans we were producing, but why. Zach recently added improved trace logging to execution planning. If I ran the query with trace logging enabled, I could diff the two outputs to see where the behavior first diverged.

Here’s the first diff between the two traces:

136834d136833

< OptimizeRoot/optimizeMemoGroup/27/optimizeMemoGroup/508/optimizeMemoGroup/460/optimizeMemoGroup/436/optimizeMemoGroup/424/optimizeMemoGroup/418/optimizeMemoGroup/326/optimizeMemoGroup/93: Updated best plan for group 93 to plan lookupjoin 31 23[mk] on movie_id_movie_keyword with cost 1640302.95As Dolt iterates over the possible plans, it keeps track of the plan with the lowest cost. Whenever it finds a new plan with a lower cost than the previous best, it replaces it and logs the change. What we’re seeing here is Dolt on Windows reporting that it found a new best plan, whereas no such report appears on Mac. All prior trace output is the same on both platforms.

This doesn’t make sense. The prior trace output contains things like:

- The cost of the new plan.

- The cost of the previous plan being replaced.

If the trace is identical prior to this point, it implies that those values are the same on both platforms. But if that’s the case, then why is only Windows switching to the new plan?

This didn’t make any sense. How on Earth could a number be less than another on Windows but not on Mac?

Just in case, I added more trace statements to report the cost of both the old and new plans:

+ m.Tracer.Log("Updated best plan for group %d from plan with cost %f to plan %s with cost %f. (%f < %f) is %t",

+ grp.Id, grp.Cost, n, grpCost, grp.Cost, cost, grp.Cost < cost)

if grp.updateBest(n, cost, m.Tracer) {

- m.Tracer.Log("Updated best plan for group %d to plan %s with cost %.2f", grp.Id, n, cost)

}And I ran the trace again:

138375c138375

< OptimizeRoot/optimizeMemoGroup/27/optimizeMemoGroup/508/optimizeMemoGroup/460/optimizeMemoGroup/436/optimizeMemoGroup/424/optimizeMemoGroup/418: Updated best plan for group 418 from plan with cost 3099284.720000 to plan lookupjoin 326 21 on movie_id_movie_info with cost 3099284.720000. (3099284.720000 < 3099284.720000) is true

---

> OptimizeRoot/optimizeMemoGroup/27/optimizeMemoGroup/508/optimizeMemoGroup/460/optimizeMemoGroup/436/optimizeMemoGroup/424/optimizeMemoGroup/418: Updated best plan for group 418 from plan with cost 3099284.720000 to plan lookupjoin 326 21 on movie_id_movie_info with cost 3099284.720000. (3099284.720000 < 3099284.720000) is falseI felt like I was losing my mind. The cost of the two plans is exactly equal, and yet they’re comparing as unequal, but only on Windows.

But the fact that they’re exactly equal is itself odd. Anyone who’s dealt with floats before knows how rare it is for two floats to be exactly equal, due to floating point error.

A quick aside about floating point arithmetic#

It’s not possible to express every possible decimal value as a floating-point, since you only have so many bits of precision. This means that the result of floating point operations need to be rounded to the nearest valid value. This is called floating point error, and causes the result of floating point operations to drift from the “true” result.

This happens in pretty much every language, because it’s a property of the IEEE-754 floating point spec, which all these languages promise to adhere to. The computations are done by the Floating-Point UNIT (FPU) included in your computer’s CPU, which also adheres to this spec.

It also means that you can’t reliably compare two floats for equality: two operations that are mathematically equivalent with real numbers won’t necessarily result in the same floats, because the operations will have different amounts of floating point error.

It turns out that Go’s print formatter is lying to us: by default, using %f causes floating point values to be truncated to 6 decimal places. If we want enough precision to ensure that different values always display unique, we can use %g instead, which reveals this in the trace:

< OptimizeRoot/optimizeMemoGroup/27/optimizeMemoGroup/508/optimizeMemoGroup/460/optimizeMemoGroup/436/optimizeMemoGroup/424/optimizeMemoGroup/418: Updated best plan for group 418 from plan with cost 3.0992847200000007e+06 to plan lookupjoin 326 21 on movie_id_movie_info with cost 3.09928472e+06. (3.09928472e+06 < 3.0992847200000007e+06) is true

---

> OptimizeRoot/optimizeMemoGroup/27/optimizeMemoGroup/508/optimizeMemoGroup/460/optimizeMemoGroup/436/optimizeMemoGroup/424/optimizeMemoGroup/418: Updated best plan for group 418 from plan with cost 3.0992847199999997e+06 to plan lookupjoin 326 21 on movie_id_movie_info with cost 3.0992847199999997e+06. (3.0992847199999997e+06 < 3.0992847199999997e+06) is falseIt turns out the costs are different after all, but the trace was truncating them. By Replacing %f with %g in existing logging statements, I was finally able to identify the first operation where the two platforms diverge. It was this simple arithmetic expression in the coster:

// read the whole left table and randIO into table equivalent to

// this join's output cardinality estimate

return lBest*seqIOCostFactor + selfJoinCard*(randIOCostFactor+seqIOCostFactor), nilAll the inputs to this expression were the same on both platforms, but the result differed by a single epsilon, the smallest possible amount that floats can differ by.

Whenever two plans had mathematically identical costs, the chosen plan would be the one that was slightly smaller due to floating point error. And changing the output of this expression by a single epsilon we enough to tip the scale on Windows.

But…

Floating point operations aren’t supposed to have different results on different platforms like this. Their behavior is unintuitive, but deterministic. A floating point operation with the same inputs should still always return the same output, even across operating systems, because both platforms conform to the IEEE spec. Consistent floating point behavior is the entire raison d’être for the spec in the first place.

There’s only two possible explanations:

- IEEE-754 does not actually guarentee consistency across platforms.

- Go does not actually conform to the IEEE-754 standard.

So which is it? I assumed this would be a simple yes-or-no question. Instead, it sent me down a rabbit hole.

The Precedent for Non-Compliance#

Let’s look at how C and Java historically handled IEE-754 compliance.

C#

C has a compiler flag called -ffast-math that speeds up math operations. But there’s a reason why the compiler doesn’t do these optimizations by default: in exchange for speed, you’re violating IEEE-754. These optimizations work by allowing the compiler to rewrite your expressions into other forms that are functionally equivalent and execute faster, but aren’t guaranteed to produce the exact same results as the original expression. For example, if you’re adding multiple values it might reorder terms as if addition is associative, even though addition is not associative under IEEE-754. As a result, your code is faster but you might accrue more error.

Or, you might accrue less error, which can be just as bad!

It might be weird to think that producing less error is a bad thing, but any result that differs from IEEE is technically changing the behavior of the program, even if it’s changing it in ways that most users wouldn’t care about.

Since these optimizations are disabled by default, the language designers are taking the stance that code should comply with IEEE by default, and only deviate when the user specifically requests speed.

Interestingly, the GCC compiler also has the -ffloat-store flag, which prevents the generated code from storing the result of a floating point operation in a register. This exists to prevent cases where the register has more precision than necessary, resulting in reduced floating point error. In this case, the flag is being used to prevent an optimization, and the default behavior is to allow results that are plaform-dependent.

Java#

Prior to Java 7, the JVM would only guarantee that floating point operations will accrue at most as much error as IEE implies, but was allowed to accrue less instead unless the strictfp keyword was used. Similar to the GCC example above, this allowed the JVM to use extended-precision registers to speed up execution while also reducing error.

This was removed in Java 7 because the two cases where it mattered were no longer commonplace:

- Storing a 32-bit float in a 64-bit register was no longer a concern due to the proliferation of 64-bit systems.

- The x87 floating point extension found in some Intel processors used 80-bit registers, but was being replaced by the SSE instruction set extension, which guarentees IEE compatibility.

What about Go?#

Finding a straight answer on whether Go allows these sort of optimizations was surprisingly challenging. The official documentation suggests that all float64 values in a Go program are valid IEEE-754 64-bit floating-point numbers, but nothing I found mentioned either of these cases specifically.

If Go adopts the same approach now as Java did back then, then that could potentially explain the difference in behavior: both versions of the program are valid realizations of the source code according to the language spec, even if one of them produces less floating-point error than IEEE-754 would imply.

But I was skeptical this was the case. Extended-precision registers seem to be a historical artifact that wouldn’t affect modern hardware, and given Go’s philosophy of safety, I would be incredibly surprised if Go’s default flags allowed optimizations that C didn’t.

Plus, that still didn’t explain why the behavior depended on the OS. Both versions were built using the same version of Go, with the same set of compiler flags. Is there some optimization that only happens on Windows vs Mac? That didn’t seem likely to me.

Finally, after more digging, I found this: https://github.com/golang/go/issues/17895, debating whether to allow the Go compiler to emit the Fused-Multiply-Add (FMA) instruction.

FMA is an CPU instruction that performns a multiply followed by an add, and only rounds to the required precision after both operations. It’s more efficient than using separate instructions for MUL and ADD, and more efficient than a non-fused Multiply–Add (MAD) instruction that rounds after each operation. It also can potentially return different results.

Also, FMA is supported on all ARMv8 chips, but only some AMD and Intel CPUs. That was the final piece of the puzzle. In my laser focus on Windows vs Mac, I’d forgotten one very important detail:

All of the Macs we use are M1 MacBooks, which famously use the ARM instruction set.

I had been so fixated on viewing this as an OS problem that I didn’t consider that the two environments also had a different CPU.

Now Recall that this was the line of code that was producing different results between the two machines:

return lBest*seqIOCostFactor + selfJoinCard*(randIOCostFactor+seqIOCostFactor), nilThat sure looks like a multiply followed by an add to me.

If the compiler was emitting this instruction, but not on AMD CPUs that didn’t support it, then all of this behavior makes sense. The ARM processor on the Mac was using the FMA instruction, which led to reduced floating-point error. This was enough to flip the comparison of two very-almost-equal costs, resulting in a different plan being selected.

I was able to confirm this by inserting an explicit cast between the multiply and the add, which according to the linked issue would prevent the FMA instruction from being generated. The line now read

return float64(lBest*seqIOCostFactor) + float64(selfJoinCard*(randIOCostFactor+seqIOCostFactor)), nilAnd with this one small change, both platforms generated the same plans, at the cost of slower performance on ARM.

Does Golang Actually Implement the IEEE-754 Floating Point Spec? They Answer Might Surprise You!#

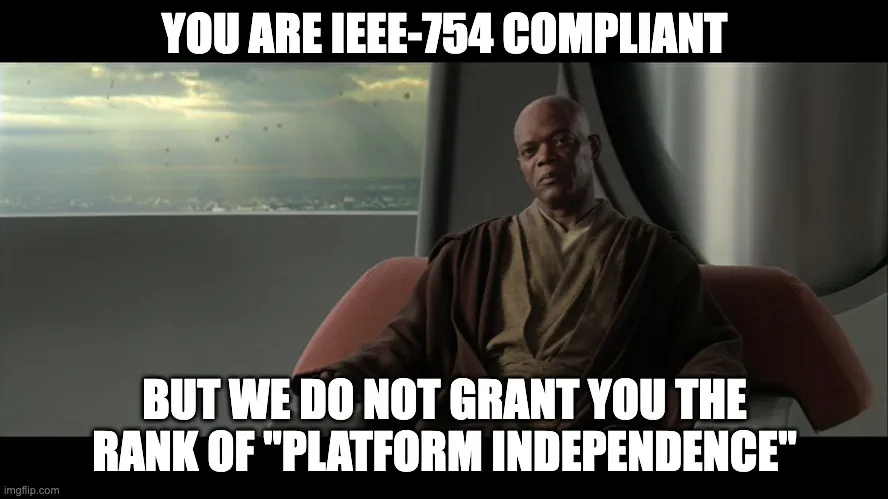

We are now finally ready to address the questions in the title of this post, along with another question: Does IEEE-754 compliance guarentee consistency across platforms?

The fact that it’s possible to write platform-dependent floating point code suggests that these statements cannot both be true. If the spec allows the Go compiler to generate Fused-Multiply-Add instructions, then IEEE-754 compliant languages are not guarenteed to be platform independent. Conversely, if the purpose of IEEE-754 is to guarentee portability, then Golang cannot possibly be in compliance. It would also mean that GCC and Java (pre Java 7) are also not in compliance.

At first glance, the answer would seem to be “None of these languages are compliant”.

Here’s a bit from “What Every Computer Scientist Should Know About Floating-Point Arithmetic”, written by the very influential David Goldberg:

One reason for completely specifying the results of arithmetic operations is to improve the portability of software. When a program is moved between two machines and both support IEEE arithmetic, then if any intermediate result differs, it must be because of software bugs, not from differences in arithmetic.

Open and shut, right?

Except, here’s an except from an addendum to that paper that was written by Doug Priest and included in “Sun’s Numerical Computation Guide”, published with David Goldberg’s permission:

The reader might be tempted to conclude that such programs should be portable to all IEEE systems. Indeed, portable software would be easier to write if the remark on page 195, “When a program is moved between two machines and both support IEEE arithmetic, then if any intermediate result differs, it must be because of software bugs, not from differences in arithmetic,” were true.

Unfortunately, the IEEE standard does not guarantee that the same program will deliver identical results on all conforming systems. […] In fact, the authors of the standard intended to allow different implementations to obtain different results. Their intent is evident in the definition of the term destination in the IEEE 754 standard: “A destination may be either explicitly designated by the user or implicitly supplied by the system (for example, intermediate results in subexpressions or arguments for procedures). Some languages place the results of intermediate calculations in destinations beyond the user’s control. Nonetheless, this standard defines the result of an operation in terms of that destination’s format and the operands’ values.” (IEEE 754-1985, p. 7) In other words, the IEEE standard requires that each result be rounded correctly to the precision of the destination into which it will be placed, but the standard does not require that the precision of that destination be determined by a user’s program. Thus, different systems may deliver their results to destinations with different precisions, causing the same program to produce different results (sometimes dramatically so), even though those systems all conform to the standard.

A language that chooses the precision of intermediate results still conforms to IEEE-754, even though it could make that decision in a platform-dependent manner, resulting in the program itself being platform dependent. It’s a pedantic distinction, but I don’t see any other way to interpret the spec.

So, does Golang actually implement the IEEE-754 floating point spec? It turns out, the answer is “yes”. It just turns out that’s not enough to make your math portable.

And if you don’t actually find that answer surprising:

(Image source: Order of the Stick #1186)

(Image source: Order of the Stick #1186)

I did say that it might surprise you.