Update: dolthub/swiss has been archived because Golang 1.24 made Swiss tables the default map implementation.

Today’s blog is announcing SwissMap, a new Golang hash table based on SwissTable that is faster and uses less memory than Golang’s built-in map. We’ll cover the motivation, design and implementation of this new package and give you some reasons to try it. This blog is part of our deep-dive series on the Go programming language. Past iterations include posts about concurrency, “inheritance”, and managing processes with Golang.

At DoltHub, we love Golang and have used it to build DoltDB, the first and only SQL database

you can branch, diff and merge. Through our experience building Dolt, we’ve gained some expertise in the language. We

found a lot of features we appreciate and a few more sharp edges that have bitten us. One of the hallmarks of the Go

language is its focus on simplicity. It strives to expose a minimal interface while hiding a lot of complexity in the

runtime environment. Golang’s built-in map is a great example of this: its read and write operations have dedicated

syntax and its implementation is embedded within the runtime. For most use cases, map works great, but its opaque

implementation makes it largely non-extensible. Lacking alternatives, we decided to roll our own hash table.

Motivation#

Hash tables are used heavily throughout the Dolt codebase, however they become

particularly performance critical at lower layers in stack that deal with data persistence and retrieval. The abstraction

responsible for data persistence in Dolt is called a ChunkStore. There are many ChunkStore implementations, but they

share a common set of semantics: variable-length byte buffers called “chunks” are stored and fetched using a [20]byte

content-addressable hash. Dolt’s table indexes are stored in Prolly Trees

a tree-based data structure composed of these variable-sized chunks. Higher nodes in a Prolly tree reference child nodes

by their hash. To dereference this hash address, a ChunkStore must use a “chunk index” to map hash addresses to physical

locations on disk. In contrast, traditional B-tree indexes use fixed-sized data pages and parent nodes reference children

directly by their physical location within an index file.

Large Prolly Tree indexes in Dolt can be 4 to 5 levels deep. Traversing each level requires using the chunk index to

resolve references between parent and child nodes. In order to compete with traditional B-tree indexes, the chunk index

must have very low latency. The original design for this chunk index was a set of static, sorted arrays. Querying the

index involved binary searching each array until the desired address was found. The upside of this design was its

compactness. Chunk addresses alone are 20 bytes and are accompanied by a uint64 file offset and a uint32chunk length.

This lookup information is significantly more bloated than the 8 byte file offset that a traditional B-Tree index would

store. Storing lookups in static arrays minimized the memory footprint of a chunk index. The downside is that querying

the index has asymptotic complexity of m log(n) where m is that number of arrays and n is their average size.

While designing our new ChunkStore implementation, the Chunk Journal,

we decided to replace the array-based chunk index with a hash table. A hash-table-based index would support constant time

hash address lookups, reducing ChunkStore latency. The tradeoff is that the hash table used more memory. Exactly

how much more memory depends on what type of hash table you’re using. Our first implementation used Golang’s built-in

hash table map which has a “maximum load factor” of 6.5/8. This meant that in the best-case-scenario map uses 23%

more memory than the array-based chunk index. However, the average case is much worse. So how could we get constant-time

chunk lookups without blowing our memory budget? Enter SwissMap.

SwissTable Design#

SwissMap is based on the “SwissTable” family of hash tables from Google’s open-source C++ library Abseil.

These hash tables were developed as a faster, smaller replacement for std::unordered_map

from the C++ standard library. Compared to std::unordered_map, they have a denser, more cache-friendly memory layout

and utilize SSE instructions to accelerate key-value lookups.

The design has proven so effective that it’s now being adopted in other languages. Hashbrown,

the Rust port of SwissTable, was adopted into the Rust standard library in Rust 1.36. There is even an

ongoing effort within the Golang community to adopt the SwissTable design

as the runtime map implementation. The SwissTable design was a perfect fit for our chunk index use-case: it was fast

and supported a higher maximum load factor of 14/16.

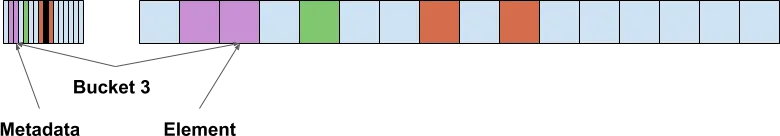

The primary design difference between the built-in map and SwissMap is their hashing schemes. The built-in map uses an

“open-hashing” scheme where key-value pairs with colliding hashes are collected into a single “bucket”. To look up a value

in the map, you first choose a bucket based on the hash of the key, and then iterate through each key-value pair in the

bucket until you find a matching key.

A key optimization in the built-in map is the use of “extra hash bits” that allow for fast equality checking while

iterating through slots of a bucket. Before directly comparing the query key with a candidate, the lookup algorithm first

compares an 8-bit hash of each key (independent from the bucket hash) to see if a positive match is possible. This fast

pre-check has a false-positive rate of 1/256 and greatly accelerates the searches through a hash table bucket. For more

design details on the Golang’s built-in map, checkout Keith Randall’s 2016 GopherCon talk

“Inside the Map Implementation”.

The SwissTable uses a different hashing scheme called “closed-hashing”. Rather than collect elements into buckets, each

key-value pair in the hash-table is assigned its own “slot”. The location of this slot is determined by a probing

algorithm whose starting point is determined by the hash of the key. The simplest example is a linear probing search

which starts at slot hash(key) mod size and stops when the desired key is found, or when an empty slot is reached. This

probing method is used both to find existing keys and to kind insert locations for new keys. Like the built-in Golang map,

SwissTable uses “short hashes” to accelerate equality checks during probing. However, unlike the built-in map, its hash

metadata is stored separately from the key-value data.

The segmented memory layout of SwissTable is a key driver of its performance. Probe sequences through the table only access the metadata array until a short hash match is found. This access pattern maximizes cache-locality during probing. Once a metadata match is found, the corresponding keys will almost always match as well. Having a dedicated metadata array also means we can use SSE instructions to compare 16 short hashes in parallel! Using SSE instruction is not only faster, but is the reason SwissTable supports a maximum load factor of 14/16. The observation is that “negative” probes (searching for a key that is absent from the table) are only terminated when an empty slot is encountered. The fewer empty slots in a table, the longer the average probe sequence takes to find them. In order to maintain O(1) access time for our hash table, the average probe sequence must be bounded by a small, constant factor. Using SSE instructions effectively allows us to divide the length of average probe sequence by 16. Empirical measurements show that even at maximum load, the average probe sequence performs fewer than two 16-way comparisons! If you’re interested in learning (a lot) more about the design of SwissTable, check out Matt Kulukundis’ 2017 CppCon talk “Designing a Fast, Efficient, Cache-friendly Hash Table, Step by Step”.

Porting SwissTable to Golang#

With a design in hand, it was time to build it. The first step was writing the find() algorithm. As Matt Kulukundis

notes in his talk, find() is the basis for all the core methods in SwissTable: implementations for Get(), Has(),

Put() and Delete() all start by “finding” a particular slot. You can read the actual implementation

here, but for simplicity

we’ll look at a pseudocode version:

func (m Map) find(key) (slot int, ok bool) {

h1, h2 := hashOf(key) // high and low hash bits

s := modulus(h1, len(m.keys)/16) // pick probe start

for {

// SSE probe for "short hash" matches

matches := matchH2(m.metadata[s:s+16], h2)

for _, idx := range matches {

if m.keys[idx] == key {

return idx, true // found |key|

}

}

// SSE probe for empty slots

matches = matchEmpty(m.metadata[s:s+16])

for _, idx := range matches {

return idx, false // found empty slot

}

s += 16

}

}The probing loop continues searching until it reaches one of two exit conditions. Successful calls to Get(), Has(),

and Delete() terminate at the first return when both the short hash and key value match the query key. Put()

calls and unsuccessful searches terminate at the second return when an empty slot is found. Within the metadata array,

empty slots are encoded by a special short hash value. The matchEmpty method performs a 16-way SSE probe for this

value.

Golang support for SSE instructions, and for SIMD instructions in general, is minimal. To leverage these intrinsics, SwissMap uses the excellent Avo package to generate assembly functions with the relevant SSE instructions. You can find the code gen methods here.

The chunk index use case requires a specific hash table mapping hash keys to chunk lookup data. However, we wanted SwissMap

to be a generic data structure that could be reused in any performance-sensitive context. Using generics, we could

define a hash table that was just as flexible as the built-in map:

package swiss

type Map[K comparable, V any] struct {

hash maphash.Hasher[K]

...

}SwissMap’s hash function is maphash, another DoltHub package that uses Golang’s

runtime hasher capable of hashing any comparable data type. On supported platforms, the runtime hasher will use

AES instructions to efficiently generate strong hashes. Utilizing

hardware optimizations like SSE and AES allows SwissMap to minimize lookup latency, even outperforming Golang’s builtin

map for larger sets of keys:

goos: darwin

goarch: amd64

pkg: github.com/dolthub/swiss

cpu: Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-9750H CPU @ 2.60GHz

BenchmarkStringMaps

num_keys=16

num_keys=16 runtime_map-12 112244895 10.71 ns/op

num_keys=16 swiss.Map-12 65813416 16.50 ns/op

num_keys=128

num_keys=128 runtime_map-12 94492519 12.48 ns/op

num_keys=128 swiss.Map-12 62943102 16.09 ns/op

num_keys=1024

num_keys=1024 runtime_map-12 63513327 18.92 ns/op

num_keys=1024 swiss.Map-12 70340458 19.13 ns/op

num_keys=8192

num_keys=8192 runtime_map-12 45350466 24.77 ns/op

num_keys=8192 swiss.Map-12 58187996 21.29 ns/op

num_keys=131072

num_keys=131072 runtime_map-12 35635282 40.24 ns/op

num_keys=131072 swiss.Map-12 36062179 30.71 ns/op

PASSFinally, let’s look at SwissMap’s memory consumption. Our original motivation for building SwissMap was to get constant time lookup performance for our chunk index while minimizing the additional memory cost. SwissMap supports a higher maximum load factor (87.5%) than the built-in map (81.25%), but this difference alone doesn’t tell the whole story. Using Golang’s pprof profiler, we can measure the actual load factor of each map for a range of key set sizes. Measurement code can be found here.

In the chart above we see markedly different memory consumption patterns between SwissMap and the built-in map. For comparison, we’ve included the memory consumption of array storing the same set of data. Memory consumption for the built-in map follows a stair-step function because it’s always constructed with a power-of-two number of buckets. The reason for this comes from a classic bit-hacking optimization pattern.

Any hash table lookup (open or closed hashing) must pick a starting location for its probe sequence based on the hash of

the query key. Mapping a hash value to a bucket or slot accomplished with remainder division. As it turns out, the

remainder division operator % is rather expensive in CPU cycles, but if divisor is a power of two, you can replace the

% operation with a super-fast bit mask of the lowest n bits. For this reason, many if not most hash tables are

constrained to power-of-two sizes. Often this creates negligible memory overhead, but when allocating hash tables with

millions of elements, the impact is significant! As shown in the chart above, Golang’s built-in map uses 63% more memory,

on average, than SwissTable!

To get around the slowness of remainder division, and the memory bloat of power-of-two sizing, our implementation of SwissMap uses a different modulus mapping, first suggested by Daniel Lemire. This idea is deceptively simple:

func fastModN(x, n uint32) uint32 {

return uint32((uint64(x) * uint64(n)) >> 32)

}This method uses only a few more operations than the classic bit-masking technique, and micro-benchmarks at just a

quarter of a nanosecond. Using this modulus method means we’re limited by the range of uint32, but because this

integer indexes buckets of 16 elements, SwissMap can hold up to 2 ^ 36 elements. More than enough for most use-cases

and well-worth the memory savings!

Give SwissMap a Try!#

Hopefully this was an informative deep-dive on hash table design and high-performance Golang. SwissMap proved to be an effective solution to our chunk index problem, but we hope it can also be a general purpose package for other performance sensitive use-cases. While it’s not an ideal fit for every situation, we think it has a place when memory utilization for large hash tables is a concern. If you have any feedback on SwissMap feel free to cut an issue in the repo. Or if you’d like to talk to us directly, come join our Discord!